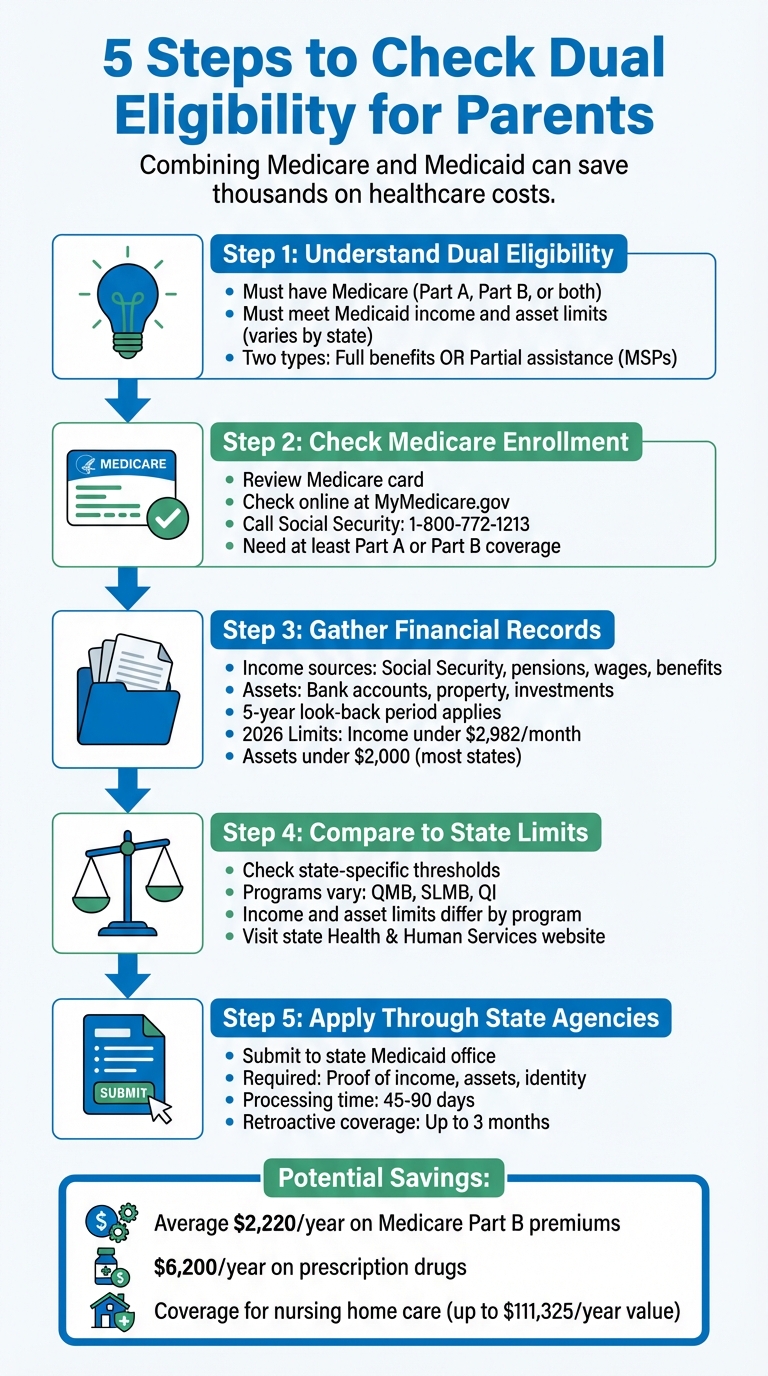

Dual eligibility can help your parents save thousands on healthcare costs by combining Medicare and Medicaid benefits. This status reduces out-of-pocket expenses like premiums, copayments, and prescription drug costs while covering services Medicare doesn’t, such as long-term care, dental, vision, and hearing aids. Here’s how to determine if your parent qualifies:

- Understand Dual Eligibility: Your parent must be enrolled in Medicare (Part A, Part B, or both) and meet Medicaid income and asset limits, which vary by state. Dual eligibility includes full benefits or partial assistance through Medicare Savings Programs (MSPs).

- Check Medicare Enrollment: Verify your parent’s Medicare status by reviewing their Medicare card or checking online at MyMedicare.gov. Ensure they have at least Part A or Part B coverage.

- Gather Financial Records: Medicaid evaluates income (Social Security, pensions, etc.) and assets (bank accounts, property) over a five-year look-back period. For 2026, most states require income below $2,982/month and assets under $2,000 for single applicants.

- Compare Finances to State Limits: Use your state’s Medicaid and MSP thresholds to determine eligibility. Limits differ for programs like QMB, SLMB, and QI, which help with premiums and other costs.

- Apply Through State Agencies: Submit applications with required documents (proof of income, assets, and identity) to your state Medicaid office. Approval can take 45–90 days, with retroactive coverage available for up to three months.

Dual eligibility can save your parent an average of $2,220 annually on Medicare Part B premiums and $6,200 on prescription drugs, while covering costly services like nursing home care (up to $111,325/year). Start by reviewing their Medicare status and financial details to explore this valuable option.

5 Steps to Check Dual Eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid

Step 1: Learn What Dual Eligibility Means

Medicare and Medicaid Basics

Medicare is a federal health insurance program designed primarily for individuals aged 65 and older, though it also covers younger individuals with specific disabilities like ALS or End-Stage Renal Disease. Medicare typically helps with hospital stays, doctor visits, and prescription medications. On the other hand, Medicaid is a joint federal and state program aimed at providing health coverage for people with limited income and resources. Each state sets its own eligibility criteria for Medicaid, which takes into account both income and assets.

Having a solid grasp of these programs is key to understanding whether your parent might qualify for dual eligibility.

Requirements for Dual Eligibility

To be considered dual-eligible, a person must already be enrolled in Medicare – whether Part A, Part B, or both – and also meet the criteria for either full Medicaid benefits or a Medicare Savings Program (MSP). MSPs include programs like QMB (Qualified Medicare Beneficiary), SLMB (Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiary), QI (Qualifying Individual), or QDWI (Qualified Disabled and Working Individual).

"People who have – or who qualify to enroll in – both Medicare and Medicaid are dual-eligible beneficiaries." – Jen Teague, Director for Health Coverage and Benefits, NCOA

There are two types of dual eligibility:

- Full dual eligibility: This means your parent qualifies for the full range of Medicaid benefits, which includes long-term care services.

- Partial dual eligibility: This applies to those enrolled in MSPs, which help cover Medicare premiums and out-of-pocket costs but don’t include full Medicaid services.

Out of the 9.7 million older adults with full Medicaid benefits, nearly half – 47% – qualify through the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) pathway.

Benefits of Dual Eligibility

Dual eligibility offers a significant financial advantage by coordinating Medicare and Medicaid benefits. Medicare serves as the primary payer, while Medicaid steps in to cover remaining costs. For those enrolled in a Medicare Savings Program, there’s an average monthly savings of $185 on Part B premiums. Additionally, the "Extra Help" program can reduce annual prescription drug costs by about $6,200.

Medicaid also fills in gaps where Medicare falls short. This includes services like routine dental exams, vision care, hearing aids, and extended nursing home care beyond Medicare’s 100-day limit. Without Medicaid, long-term nursing home care could cost as much as $111,325 per year.

sbb-itb-48c2a85

Step 2: Check Your Parent’s Medicare Status

How to Check Medicare Enrollment

Before diving into dual eligibility, it’s essential to confirm whether your parent is enrolled in Medicare. The easiest way? Look for their physical Medicare card. This card provides their Medicare number and the start dates for both Medicare Part A (hospital insurance) and Part B (medical insurance).

Can’t find the card? No problem. You can log in to MyMedicare.gov or their Social Security account to check their enrollment status. Alternatively, use the Medicare.gov tool by entering the necessary details. If online access isn’t an option, you can call the Social Security Administration directly at 1-800-772-1213 to confirm their Medicare status.

Here’s a tip: If your parent was already receiving Social Security benefits before turning 65, they were likely enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B automatically. In such cases, the Medicare card typically arrives in the mail about three months before their 65th birthday.

Once you’ve verified their enrollment, take a closer look at their Medicare coverage type to ensure it aligns with dual eligibility requirements.

Medicare Types Explained

Knowing the type of Medicare your parent has is a key part of determining dual eligibility. Here’s a quick breakdown:

- Original Medicare: This includes Part A (hospital insurance) and Part B (medical insurance). Part A covers inpatient hospital stays, skilled nursing care, and hospice services, while Part B handles doctor visits, outpatient care, and medical equipment.

- Medicare Advantage (Part C): This option combines Parts A and B, often with added prescription drug coverage. If your parent has a card from a private insurer rather than the standard Medicare card, they are likely enrolled in Medicare Advantage.

Both types of coverage – Original Medicare and Medicare Advantage – qualify for dual eligibility as long as they include at least Part A or Part B. That’s why confirming the exact coverage type is such an important step.

Who Qualifies For Dual Eligibility? – CountyOffice.org

Step 3: Collect Income and Asset Information

Once Medicare is squared away, it’s time to dive into financial records. Medicaid eligibility hinges on strict income and asset limits, so you’ll need to document your parent’s financial history from the past five years.

Medicaid conducts a five-year “look-back” to ensure no assets were transferred just to meet eligibility requirements. States cross-check the information you provide with financial institutions and public records.

To make this process smoother, organize all income and asset documentation clearly and systematically.

Income Sources to Document

Medicaid considers certain types of income when determining eligibility. You’ll need to gather records for countable income sources, including:

- Social Security benefits

- Disability benefits

- Veterans benefits

- Wages

- Pensions

- Withdrawals from retirement accounts

To verify these amounts, secure official award letters from agencies like Social Security, Railroad Retirement, or Veterans Affairs (VA).

However, not all income counts. Medicaid typically excludes payments such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI), SNAP (food stamps), federal housing assistance, and energy assistance. For 2026, the monthly income limit for a single senior applying for Nursing Home Medicaid or Home and Community-Based Services waivers is $2,982 in most states.

To ensure accuracy, collect pay stubs, benefit statements, and five years of bank records. Also, check with your local Medicaid office for any state-specific rules that might affect income calculations.

Countable vs. Non-Countable Assets

After documenting income, turn your attention to assets. In most states, a single applicant can have up to $2,000 in countable assets to qualify for long-term care Medicaid. Some states have higher limits – for instance, California allows up to $130,000, while New York permits up to $32,396.

Countable assets typically include:

- Cash savings and checking accounts

- Stocks, bonds, and certificates of deposit (CDs)

- Real property (other than the primary residence)

- Additional vehicles beyond the first one

In many states, IRAs and 401(k)s are also considered countable assets.

On the other hand, non-countable (exempt) assets usually include:

- The primary residence (if the applicant or certain family members live there)

- One vehicle, regardless of value

- Personal belongings and household goods

- Term life insurance policies

- Burial plots

Life insurance policies with a face value under $1,500 and up to $1,500 set aside for burial expenses are also exempt.

To streamline the verification process, gather bank statements for checking, savings, money market accounts, and CDs covering the five-year look-back period. Contact insurance providers for statements showing policy face values and cash surrender values. If accounts have been closed or assets transferred in the past five years, keep the closing documents handy.

If your parent’s assets exceed the eligibility limits, consider consulting a Medicaid Planner. They can advise on legal strategies like Irrevocable Funeral Trusts or Medicaid Asset Protection Trusts. For example, converting countable cash into an irrevocable funeral trust (IFT), which is generally exempt up to state-specific limits (often around $15,000), might be a practical solution.

Step 4: Compare Finances to Medicaid and MSP Limits

Now that you’ve documented your parent’s income and assets in Step 3, it’s time to see how their finances stack up against program limits. This involves comparing their financial situation to eligibility thresholds for programs like full Medicaid, Qualified Medicare Beneficiary (QMB), Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiary (SLMB), and Qualifying Individual (QI). Getting these comparisons right is crucial for securing dual eligibility benefits.

The income and asset limits vary depending on the program and your parent’s household status. For instance, Nursing Home Medicaid or Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) Waivers in 2026 typically allow up to $2,982 per month in income for a single senior. On the other hand, Regular Medicaid (for Aged, Blind, and Disabled individuals) often sets income limits between $994 and $1,305 per month. For Medicare Savings Programs (MSPs), the limits are tied to the Federal Poverty Level (FPL): QMB equals 100% of FPL plus $20, SLMB equals 120% of FPL plus $20, and QI equals 135% of FPL plus $20. To make accurate comparisons, you’ll need to check your state’s specific thresholds and summarize them in a table.

How to Find State-Specific Limits

To get the most accurate information, visit your state’s Health and Human Services website. For example, if you’re in Texas, you can use the "Your Texas Benefits" site to find the latest limits.

"Although Medicaid income limits are primarily based on the federal poverty level (FPL), states have the freedom to set their own limits and even create different categories of eligibility." – Ryan Ramsey, NCOA Associate Director of Health Coverage and Benefits

Some states apply stricter criteria than federal standards. Others, like California, have much higher asset limits – $130,000 compared to the typical $2,000. If your parent’s income exceeds the standard thresholds, look into whether your state offers a "Medically Needy" or "Spend Down" option. These pathways allow medical expenses to be deducted from income to meet eligibility requirements.

Creating a Comparison Table

Once you’ve confirmed your state’s specific limits, organize the information into a comparison table. Include your parent’s countable monthly income and countable assets in one column, and the eligibility thresholds for each program in adjacent columns. Here’s an example of what the limits might look like for a single individual in 2026:

| Program Type | Monthly Income Limit | Asset Limit |

|---|---|---|

| Nursing Home / HCBS | $2,982 | $2,000 (most states) |

| Regular Medicaid (ABD) | $994–$1,305 | $2,000 |

| QMB (MSP) | ~$1,325 | ~$9,660 |

| SLMB (MSP) | ~$1,585 | ~$9,660 |

| QI (MSP) | ~$1,781 | ~$9,660 |

This table will give you a clear snapshot of how your parent’s finances compare to the eligibility requirements, helping you identify the most suitable programs.

Step 5: Confirm State Rules and Apply

After comparing your parent’s finances to the thresholds outlined in Step 4, it’s time to confirm the specific rules in your state and start the application process. Medicaid and Medicare Savings Programs differ from state to state, so eligibility requirements can vary widely.

"The rules around who’s eligible for Medicaid are different in each state." – Medicare.gov

Checking Eligibility with State Agencies

Your first step should be reaching out to your State Medical Assistance (Medicaid) office or visiting a local Aging and Disability Resource Center (ADRC). These agencies can help clarify which types of income and assets are considered for eligibility. For instance, some states exclude specific income sources or allow higher asset limits than the federal baseline.

"You may still qualify for these programs in your state even if your income or resources are higher than the federal limits listed." – Medicare.gov

If your parent’s income slightly exceeds the limit, ask about "medically needy" or "spend-down" programs. These programs, available in 36 states and the District of Columbia, allow individuals to qualify by offsetting income with medical expenses. Additionally, be aware of Medicaid’s 60-month "look-back" period for long-term care services, which examines any significant asset transfers to ensure they weren’t sold or gifted below market value.

Once you’re clear on your state’s rules, you can start gathering the necessary documents for the application.

Preparing and Submitting Applications

Before applying, collect all required documentation. This typically includes:

- Proof of identity: Birth certificate, driver’s license, or passport

- Proof of residence: Rent receipts, property tax bills, or deeds

- Income verification: Social Security award letters, pay stubs, or pension statements

- Asset documentation: Bank statements, life insurance policies, or real estate appraisals

Applications can be submitted online, by phone, in person, or by mail. Online applications are usually the quickest option and often provide immediate confirmation of receipt. If your parent is already receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI), check with your local Medicaid office – they may already be enrolled automatically.

State agencies typically take 45–90 days to process applications, depending on whether disability determinations are involved. You can track the status of your application through the state portal or by contacting the Medicaid office directly. Once a decision is made, you’ll receive a formal letter detailing the coverage start date and any cost-sharing responsibilities. If the application is denied, you have the right to appeal and request a fair hearing, usually within 30 to 90 days of receiving the denial notice.

If approved, Medicaid can retroactively cover up to three months of medical expenses.

How ElderHonor Can Help

Navigating dual eligibility for Medicaid and Medicare Savings Programs can feel overwhelming, but ElderHonor offers tools to simplify the process. By focusing on financial organization and personalized support, they make it easier to manage the complexities of documentation and state-specific requirements.

ElderHonor Toolkit for Financial Organization

The ElderHonor Toolkit includes worksheets and modules designed to help you gather and organize the financial documents needed for applications. It helps categorize income and assets into countable and exempt groups – a key step when comparing your parent’s income to the 2026 limit of about $2,982 per month for many programs.

For example, the toolkit breaks down countable assets (like cash, stocks, bonds, and non-primary real estate) versus exempt assets (such as a primary home, one vehicle, and up to $1,500 in burial funds). Since state agencies often require at least three months of bank statements and detailed asset records, having a structured approach can save time and reduce the risk of delays.

Additionally, the toolkit tracks medical expenses for spend-down eligibility. This is especially helpful when high medical bills can be deducted from income to meet eligibility requirements. For families facing significant long-term care costs, this feature can make a big difference.

For situations that go beyond standard cases, ElderHonor also provides tailored support.

Personalized Coaching for Complex Cases

If your parent’s financial or health situation is more complicated – such as when income is near eligibility thresholds or they have multiple chronic conditions – ElderHonor’s personalized coaching offers targeted, one-on-one assistance.

Coaches can guide you through tricky scenarios, like retroactive coverage for past medical expenses, and help you prepare a strong appeal if an application is denied. Since Medicaid decisions can take up to 45 business days, having expert advice ensures your documentation is accurate and complete, smoothing the entire process.

Conclusion

To determine dual eligibility, start by understanding the basics of Medicare and Medicaid. Next, confirm your parent’s Medicare status, collect their income and asset information, compare these details to your state’s eligibility limits, and submit applications through the appropriate state agencies.

Dual eligibility provides critical financial relief for 13.7 million older adults, saving an average of $2,220 annually on Medicare Part B premiums and reducing prescription drug expenses by $6,200 per year. This is especially crucial for parents with long-term care needs, as Medicare only covers up to 100 days of skilled nursing care, while private nursing home costs can skyrocket to $111,325 annually. These numbers highlight both the advantages and the complexities of navigating dual eligibility.

"Dual eligibility is an important way many older adults can expand their health care benefits and protect their financial well-being. But the rules can be complicated." – Ryan Ramsey, NCOA Associate Director of Health Coverage and Benefits

Careful preparation is essential. Make sure all documentation is in order and familiarize yourself with your state’s specific requirements. Free resources like the State Health Insurance Assistance Program (SHIP) provide one-on-one counseling, while tools such as the ElderHonor Toolkit can help you organize financial paperwork to ensure nothing gets overlooked.

FAQs

What are the advantages of being eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid?

Being eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid can greatly lower out-of-pocket expenses. This includes coverage for things like Medicare premiums, deductibles, copayments, and other cost-sharing responsibilities. On top of that, it opens the door to services that Medicare doesn’t typically cover, such as nursing home care, personal care services, and expanded long-term care options.

This combination of benefits not only eases financial strain but also provides access to a wider range of health care services. For aging parents navigating medical and personal care needs, this dual coverage can make a world of difference.

How do I check if my parent is enrolled in Medicare?

To check if your parent is enrolled in Medicare, you’ll need their full name, Social Security number, and date of birth. You can verify their enrollment by logging into their account on the Social Security website or Medicare.gov. If online access isn’t an option, you can call Medicare directly at 1-800-MEDICARE (1-800-633-4227) for help. Make sure to keep any verification materials, like a benefits letter or a copy of their Medicare card, for your records.

What financial documents are needed to determine dual eligibility for my parents?

If you’re trying to figure out whether your parents qualify for dual eligibility, the first step is collecting the right documents. You’ll need income records like pay stubs, Social Security benefit statements, or tax returns. On top of that, you’ll want to gather asset documentation, which could include bank statements, property records, or details about savings and investments.

Keep in mind that requirements may differ depending on the state. To avoid any confusion, it’s smart to contact your local Medicaid office or a reliable resource to get a clear list of what’s needed for the application.